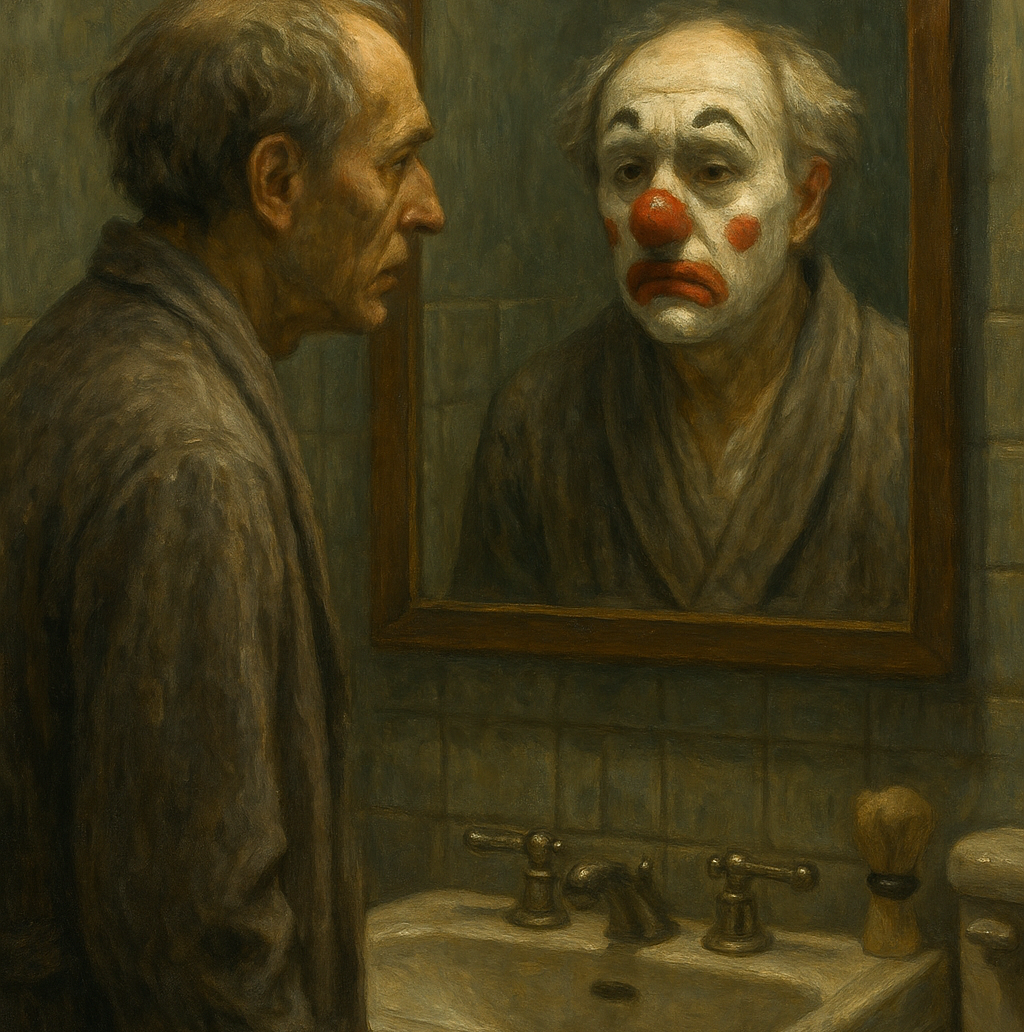

On the morning of his retirement, Dr Emil Voran—a lifelong mathematician and servant of pure logic—looked into his bathroom mirror and saw a clown staring back. In that moment, he realised with unbearable clarity that everything he had built was not a legacy of intellect, but the long, unbroken performance of a joke he had never understood.

The Last Formula

On the morning of his retirement, Dr Emil Voran awoke at precisely 5:47 a.m., as he had done every weekday for the last forty-three years, seventeen days, and (as of that morning) twelve hours. There was no alarm; his body, like a disciplined metronome, simply knew. The city beyond his window was still in shadow, its buildings vague silhouettes against a cloud-laden sky. Rain tapped at the glass with the caution of someone unsure whether to knock or retreat.

He sat upright without ceremony. His room was sparse—ascetic, almost cruel in its refusal of comfort. A single bookshelf stood against the wall, filled with titles that read like confessions in an ancient language: On the Determinacy of Infinite Sets, Notes Toward a Formal Ethics of Quantification, Volume III: Theoretical Structures of the Unknowable. Each spine worn, annotated in pencil, not for decoration but for testimony.

He crossed the room to the kitchenette, where the kettle, already filled from the night before, was set to boil. He placed two slices of rye into the toaster—untoasted bread offended him philosophically—and retrieved his battered leather notebook from the top drawer. Today, he would write nothing in it. The notebook, like him, was now obsolete.

It was the end. Not of life, he reminded himself sternly—he was only seventy-two—but of purpose, of structure. The Institute would carry on, of course. It always did. Voran’s theories would be archived, his lectures catalogued, his name appended to a wing or corridor that students would pass without recognition. He would become a footnote in the grand theorem of state-sponsored knowledge.

He did not fear irrelevance; he had prepared for it as he had prepared for everything else—with rigour, calculation, and silence.

But as he stood in the bathroom, brush in hand, mirror before him, he felt something unprepared emerge—not a thought, exactly, but an unease. He raised the razor to his face, lather already applied, and glanced up to align the blade with his cheek.

And paused.

The hand stilled.

The mirror, once a mere necessity of hygiene, now confronted him with the inexplicable. The man staring back was not Dr Emil Voran.

He wore Emil’s grey dressing gown, yes. His eyes were Emil’s—dark, heavy-lidded, circled with years of insomnia and sterile lamplight. But the skin around those eyes was white—chalk white—and cracked in places, like a poorly applied theatre mask. His lips were unnaturally red, stretched into an involuntary grin. And at the centre of his face, round and glossy, perched a red rubber nose.

He blinked. The image did not change.

He leaned closer. The face in the mirror leaned too, the grin unwavering, the painted lines unmoved.

“No,” he whispered, stepping back as if from a hot stove. “No. No.”

He looked away—at the towel rack, the toothbrush holder, the damp corner of the ceiling. Rationality reasserted itself like a bureaucrat pushing through a crowd.

“A dream. A brief lapse. Neurological. Temporary.”

He turned back.

The clown stared.

The rain outside grew louder, or perhaps the silence within had simply made it so. He reached out, not to touch the mirror, but to steady himself against the sink. His fingers trembled. Dr Emil Voran did not tremble.

He tried to wipe the mirror, suspecting fog, some trick of condensation—but the cloth passed across the glass without resistance, and the clown did the same, mocking his gestures in perfect synchrony.

For the first time in decades—perhaps in his entire life—he felt absurd. Not in theory, not in humour, but in essence. It was as if the logical scaffolding that had supported him had been quietly removed during the night, and now he stood not on marble but on sawdust.

His mouth was dry.

He left the bathroom without shaving.

The Reflection

He sat at his small kitchen table, staring into his tea as though it contained some sediment of explanation. The cup trembled slightly in his hand. The room, usually his fortress of order and morning ritual, now felt alien—imbued with a quiet malice. The kettle let out the occasional metallic ping as it cooled, like a machine catching its breath after revealing a secret.

Emil’s gaze shifted to the bookshelf. The spines were unchanged, still bearing titles that once defined his identity. But something had shifted in their presence. A sense of parody hung over them, as if they were elaborate props in a poorly conceived stage play: Reflexive Topologies of Doubt, Structures Without Substance, The Hysterics of Prime Numbers. Had those always been the titles? He squinted. No, The Hysterics couldn’t be right.

He stood abruptly. The chair scraped the floor with a shriek that startled him. He crossed the flat and entered the study—his sanctum, untouched by anything as trivial as personality. Here, among notes, chalkboards, and ordered stacks of work, reality would reassert itself.

But the boards were blank.

Not erased. Not overwritten. Simply blank. As though the equations he had inscribed there night after night—proofs that had consumed his vision, his bones, his breath—had never existed. He walked to one of the filing cabinets and pulled open the top drawer.

Inside were empty folders. Page after page of nothing. Labels affixed to the fronts—“Gödel Extensions (Personal)”, “State Series: Project Delta”, “Hypernull Probabilities”—but each folder opened like a joke with no punchline. He checked another, and another. All blank.

“No,” he muttered. “No, this isn’t—this isn’t rational.” He closed the drawer, then opened it again.

Still blank.

A sharp laugh burst from him—short, involuntary, and brittle. It echoed unnaturally, as if the flat were larger than before. He clapped a hand to his mouth.

In the hallway mirror, just beyond the edge of the study door, he glimpsed the clown again.

He turned his head slowly. The figure in the mirror did not wait for his movement, but tilted its head a fraction of a second earlier. The effect was unmistakable. It was not mimicking him. It was watching him.

He backed away, heart pounding. “I’m ill,” he whispered, though he already knew the falsity of that comfort. “A transient delusion. Possibly neurological. Hallucination. Hallucinations can be rationalised.”

But no amount of logic erased the smear of white greasepaint across his mental landscape.

For a moment, a part of him clung to the idea that this was a dream—some elaborate, symbolic distortion of waking life. Perhaps his subconscious had decided to protest his retirement with metaphorical flourish. But he had always distrusted dreams. They lacked accountability.

He returned to the study and sat at the desk. He reached for a pen and began to write in the margin of an old envelope, the only scrap of paper he could find:

Hypothesis: The world has changed.

Alternate hypothesis: I have changed.

Alternate alternate hypothesis: I was never what I believed I was.

The final line stopped him. He stared at it. Then, in small, uncertain letters, he added:

The joke is not new. Only the laughter is delayed.

The laughter. That thought struck him like cold water.

There had been laughter—snatches of it, over the years. In meetings, after he left the room. In lectures, at the back of the hall. He had assumed it was unrelated. Young people laughing at something trivial. He had always been separate from them. Above them.

But what if they had been laughing at him?

He stood again, unsure of where he was walking, only that movement felt preferable to stillness. His reflection followed him from room to room, smiling, always smiling, as if amused by the notion of dignity.

Eventually, he found himself before the wardrobe. Inside, among neatly pressed shirts and identical grey trousers, was a small wooden box he hadn’t opened in years. A relic of childhood, perhaps. A gift from a cousin. He had forgotten it.

His hands moved of their own accord.

He lifted the lid.

Inside: a red rubber nose, flaking slightly with age. A pair of white gloves. A tarnished brass whistle. A painted mask with a rictus smile.

He stared.

A memory returned, sudden and unbidden—he, at six or seven, standing on a makeshift stage at school, made to perform for the others. Dressed in polka dots. Stumbling. Laughing. The others laughing. His mother clapping, but her face unreadable.

He had forgotten that.

Or buried it.

“I was a clown,” he said aloud. The words hung in the air, absurd, undeniable.

No.

I am a clown.

The Catalogue of Jokes

The hours passed unnoticed. Outside, the rain had thinned to a mist that clung to the glass like breath. Within, Dr Emil Voran sat in his armchair as if it were a witness stand, hands resting on his knees, staring into the dimness of his flat.

What remained of reason fought on, battered but dogged. “Let us proceed,” he whispered, not to any person but to the process itself, that sacred calculus of the mind which had long served as both sword and shield.

He rose and made for the filing cabinet once more.

This time, he opened the second drawer.

Inside, to his astonishment, were documents. Not blank. Not folders. Loose sheets, many crumpled and stained, bearing what at first seemed to be equations.

He seized one, flattening it on the desk. A familiar scrawl of symbols met his eyes—but something was wrong. The logic bent at strange angles. The symbols formed patterns that, upon closer inspection, resembled caricatures: the integral sign arched like a hunched back, Greek letters twisted into eyes and noses. One page bore a perfect series of sequentially increasing errors, a proof that proved only its own failure.

He rifled through them—dozens, then hundreds of pages. Some written in childish handwriting. Others laced with doodles: elephants on unicycles, juggling matrices, topological spaces wearing bow ties.

His breath caught. This wasn’t satire laid atop genius. It was the genius. These were the theorems he had submitted. He recognised his own marginalia, his signature, the institutional stamps of approval.

And they were nonsense. Structured, elaborate, peer-reviewed nonsense.

He dropped the papers and staggered back. “No—no, this cannot be. These must be forgeries. Parodies. Fabrications left by… someone.” But who? The idea of malice presupposed a world in which he mattered. That, too, now came under suspicion.

He turned on the radio—an old analogue set, kept only for its ritual hum—and turned the dial. Static. More static. Then, a voice:

“Coming up: a celebration of Dr Emil Voran’s extraordinary career in theoretical mathematics. A lifetime of service to absurdity—pardon, to academia…”

He shut it off.

He moved to the bookshelf. He pulled a volume at random—The Architecture of Silent Numbers. His name was on the cover. Inside: a preface by a former colleague lauding Voran’s “daring investigations into the intersections of formal language and interpretive instability.” He flipped to a chapter titled “Laughter in Prime Intervals.” The opening paragraph read:

“Let us suppose the number 3 is not a number at all, but a punchline delayed until comprehension lapses…”

He slammed it shut.

A thought crept in, uninvited but impossible to resist: They all knew.

The students, who smiled too broadly after lectures. The administrators, who praised his “unorthodox rigour.” The occasional journalist who interviewed him and struggled not to laugh when he described his “Hypothesis of Recursive Absurdity.”

He walked to the window. A figure stood across the street: a man in a long coat, holding an umbrella. Watching. Behind him, a parked van—painted in cheerful colours. Red, yellow, blue. A name scrawled on the side in looping script:

INSTITUTE OF COMEDIC RESEARCH – FIELD DIVISION

The man raised his hand. Not in greeting, but in slow applause.

Voran closed the curtains.

Back inside, the room seemed smaller. The walls leaned in, conspiratorial. He opened his wardrobe again and stared at the clown mask.

It stared back.

And slowly, as if pulled by some thread of inevitability, he put it on.

The Visit

By the following morning, Emil had ceased to move with intention. He walked from room to room like an actor whose lines had been stripped from the script but who remained compelled to perform. The mask lay on the table now—its painted grin beginning to feel like a premonition more than an object. He did not put it on again, but he did not return it to the box.

He made no tea. He did not eat. Hunger had become irrelevant, as if even his body now obeyed a logic alien to its biology.

Then—a knock.

Three sharp taps at the door.

Emil froze.

It was not the knock of a delivery, nor of the bored bureaucrats from the Institute, nor of neighbours. It had rhythm. Intention. The rhythm of someone who already belonged inside.

He opened the door.

There stood Sofia Mertens, once his most promising student—perhaps the only one who had ever truly listened to his lectures without a trace of irony. She looked exactly as he remembered her: severe spectacles, rain-slicked coat, notebooks clutched tightly to her chest. But her smile—was it always that wide?

“Professor Voran,” she said brightly, stepping past him without waiting for an invitation. “How wonderful. I was certain you’d still be here.”

Emil shut the door slowly. “Sofia. I hadn’t expected… anyone.”

She looked around the flat with exaggerated appreciation, nodding as though inspecting a stage set. “Just as I imagined. Monastic. Wistful. Perfectly tragic.”

He frowned. “Tragic?”

She turned. “Yes. In the aesthetic sense, of course.” Then, seeing the confusion still on his face, she added: “I came to bring you a gift.”

She reached into her satchel and drew out something bright—a balloon, twisted into the crude shape of an animal. A dog, perhaps. Or a rabbit. She held it out with both hands, solemnly.

Emil stared at it.

“You’re mocking me,” he said, voice low.

“Not at all.” She tilted her head. “You taught us everything. The importance of structure, of silence, of… timing.”

“Timing,” he repeated, uncertain.

She nodded. “You always knew when to pause. When to let the absurdity breathe. You were never afraid of nonsense. That’s what made you a master.”

He sank slowly into the chair. “No,” he whispered. “You believed in my work. You defended it. You submitted with me for the Northern Prize.”

Sofia smiled. “Of course. I loved your work. The same way one loves a finely tuned farce. The depth of the illusion, Emil—it was breathtaking.”

He looked at her, stricken. “Then you… knew?”

Her expression softened—not in pity, but in admiration. “I think some of us suspected. But only you could have lived the joke from inside. That’s what made it true art. You weren’t performing it. You were being it.”

He leaned forward, gripping the table. “I was a mathematician.”

“You were a genius,” she said. “In a field of your own making.”

They sat in silence. The rain began again, softer now, like the background hiss of an audience awaiting the next act.

Sofia stood. “I won’t take more of your time. But I do hope you’ll come out eventually. They’re setting up the tent. Everyone’s very excited.”

“The tent?”

She nodded, already halfway to the door. “Just behind the Institute. Red and white. You’ll recognise it.”

She left the balloon animal on the table beside the mask and walked out without looking back.

Emil sat there, surrounded by silence, and for the first time allowed himself to cry.

It was not weeping, not catharsis.

It was laughter turned inside out.

The Collapse

He did not sleep that night. Sleep requires a boundary—between day and night, between self and not-self—and Emil had lost all such distinctions. He sat by the window, curtain half drawn, watching the street below. At some point in the early hours, a van passed—slowly, deliberately. Painted in the same red-and-white stripes Sofia had spoken of. On its side: “THE INSTITUTE OF COMEDIC RESEARCH – RETROSPECTIVE TOUR.”

The tyres made no sound.

By dawn, he was already dressed—though not as himself. The trousers were striped, ill-fitting. His shirt had ruffles he did not remember owning. His shoes were mismatched. He had not chosen these clothes; they had simply appeared in his wardrobe during the night.

He left the flat without locking the door.

The streets of the city, once cold and grey, now appeared subtly askew. A lamppost bent at an odd angle, leaning in as though eavesdropping. Road signs bore warnings like “CAUTION: IRONY AHEAD” and “YIELD TO PARADOX”. People moved with theatrical deliberation, and every face he passed seemed… familiar. Not familiar as individuals, but as types—each one a character he could name without knowing: The Sceptic. The Plant. The Stooge. The Pantomime Bureaucrat.

At the entrance to the Institute, he paused.

Where once stood the brutalist façade of concrete and severity, now rose a large, striped tent—its peak obscured by mist, its entrance flanked by velvet ropes and a hand-painted sign:

“Dr Emil Voran: The Final Routine”

One night only. Seating limited. Applause not guaranteed.

He entered.

Inside was not a performance hall, but a warped version of the lecture theatre he had once commanded: benches, blackboard, projection equipment—but all distorted, circus-like. The lights flickered. A unicycle leaned against the podium.

Emil approached the blackboard.

Written in chalk, as though awaiting his arrival:

Let E be a set of all truths presumed serious.

Let J be a function from E to ℵ₀ such that every proof ends in laughter.

Q.E.D.

He stared at the board. His hands shook.

“I never proved anything,” he muttered.

From the shadows, a voice answered—his own voice, echoing, detached:

“You proved the impossibility of seriousness in a world that demands it.”

He turned, but the theatre was empty.

Or nearly.

In the back row sat a few figures—blurry, exaggerated, dreamlike. One clapped slowly, rhythmically. Another honked a horn. A third held a sign that read simply: “MORE!”

Emil stumbled back into the city, hoping to lose himself in its alleys and tramlines. But the more he walked, the less the city resembled anything at all. Shops now sold invisible goods. A policeman directed traffic while balancing a pie on his head. He passed a philosopher shouting at pigeons about the square root of despair.

At one point, he found himself at the Central Library.

He entered, breathless, seeking proof.

Inside, the architecture was unchanged—but the contents were not. Row after row of books bore titles like:

The Idiot’s Guide to Metaphysical Buffoonery

Set Theory for Sad Clowns

A Brief History of Prolonged Misunderstanding

Volume XIV: Jokes Without End

He ran his fingers along the shelves until one volume stopped him cold:

Voran, Emil. Collected Nothings.

He opened it.

Blank.

Page after page.

At the back, a single handwritten note:

You’ve always been funny. You just didn’t get the joke.

Emil closed the book and sat down at one of the long oak tables. His reflection in the polished surface showed the clown again. But this time, it wasn’t smiling. It was staring at him—tired, disappointed, deeply familiar.

For the first time, Emil didn’t look away.

He nodded.

The Final Theorem

It was sometime near midnight—though time, by now, had lost its substance—when Emil returned to his flat. Or rather, what remained of it.

The flat had changed.

Not in layout, but in tone. The walls had softened, their corners rounded, the colours faintly brighter, like the interior of a nursery or a set from a silent film. The furniture had subtly shifted. The chair was now a low wooden stool with squeaky springs. The bookshelf contained only rubber chickens and volumes with spinning wheels on the covers. The desk, once a site of furious thought, now resembled a magician’s table, complete with top hat and wand.

Only the mirror remained unchanged. Cold. Unflinching. True.

Emil approached it slowly, like a man returning to the scene of a crime he both remembers and denies. The reflection greeted him with its painted face, its drooping eyes, its heavy red grin.

But now there was something else.

Recognition.

Not mockery. Not surprise.

The clown in the mirror was not an impostor. It was not laughing at him. It was him—exhausted, unmasked by the very mask it wore.

He opened his notebook one final time. Not the real one—he had long since misplaced that in his collapse—but a child’s composition pad, filled with faintly lined pages and a sticker on the front that read: YOU TRIED.

He turned to a fresh page and picked up the crayon resting beside it—blue, dull at the tip. And he began to write, slowly, carefully:

THE FINAL THEOREM

Let MMM be the man.

Let CCC be the clown.

Let TTT be time, undefined.

Assume: M≠CM \neq CM=C.

Suppose: MMM builds structures to escape the absurd.

Observe: All such structures are absurd.

Then: M=CM = CM=C.

Therefore:

Q.E.D. — I am not the clown. The world is.

He stared at the sentence. Then, for the first time in his life, he smiled—not with bitterness, not with irony, but with acceptance. A quiet, tragic joy.

He stood and went to the wardrobe. The clown’s costume hung ready. He dressed slowly. With ceremony. As a priest dons vestments before the final mass.

The last thing he put on was the red nose.

He turned to the mirror.

The clown bowed.

Then stepped out into the hall.

Down the stairs. Through the door. Into the dark.

Somewhere, faintly, the sound of an audience rustled to life—throats clearing, programmes opening, shoes shifting on the floor. Then the soft, anticipatory silence before a curtain rises.

Emil stepped into the streetlight.

He juggled nothing.

And they laughed.